Last Updated:

January 30th, 2026

Pica

It’s not unusual to reach for ice cream when we feel down, and it’s just as common to crave delicious foods when we’re happy. But what happens when we replace the foods in those moments with objects? This is where things begin to feel unusual for most people, yet for some, it’s their everyday reality. Pica is an eating disorder that leads to cravings for items that aren’t meant to be eaten, and on this page, we explore what the condition involves. We also offer guidance on how to get support for pica, so if you recognise any of these signs in yourself or someone you care about, you’ll know where to turn next.

What is pica?

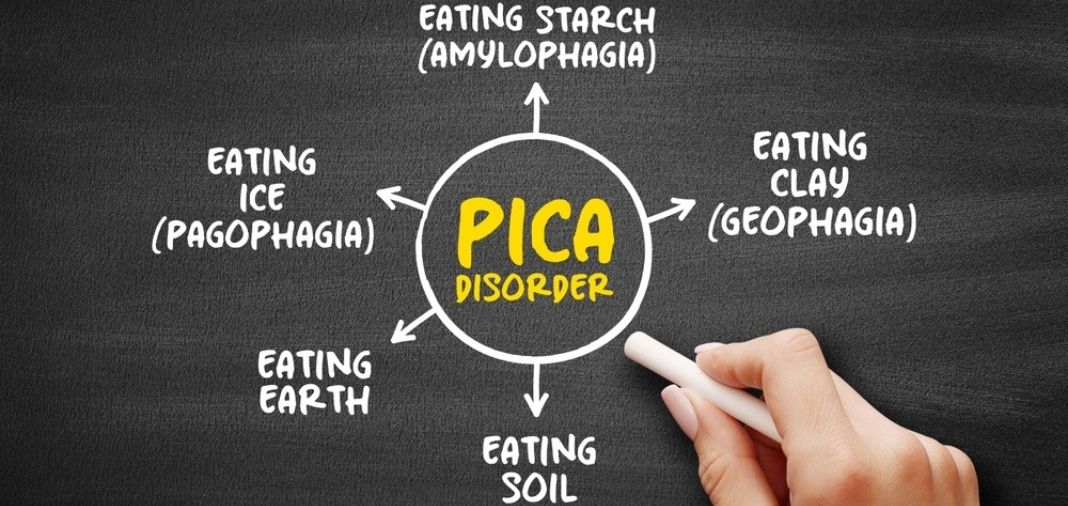

Pica is a condition where a person repeatedly eats non-food, non-nutritive items for at least one month. These substances hold no nutritional value and are not considered edible, yet the urge to consume them can be strong and difficult to manage.

People with pica may eat things such as:

- Paper

- Chalk

- Soil

- Soap

- Hair

- Ash

- Clay

- Cloth

The specific items vary widely from person to person, which is one reason why pica is sometimes overlooked or misunderstood.

Is pica classed as an eating disorder?

The DSM-5 recognises pica as an eating disorder when the behaviour meets specific criteria. The behaviour must be persistent, inappropriate for the person’s developmental stage and not part of a cultural or socially accepted practice. If pica occurs alongside another mental-health or medical condition, it must be severe enough to require separate clinical attention.

It’s important to remember that a behaviour can look unusual from the outside yet still have deep emotional or biological roots. This is why a proper assessment is essential, as the underlying reason isn’t always obvious without professional input.

What causes pica?

Pica doesn’t have one single cause and instead, develops through a potential mixture of biological, psychological, developmental and environmental factors.

For example, one theory points to nutritional deficiencies, particularly shortages of iron or zinc. When the body lacks certain minerals, cravings may shift toward substances that symbolically resemble what’s missing, even though they cannot provide the nutrients needed. During pregnancy, these deficiencies may be amplified, leading to cravings for items like clay or charcoal.

Developmental differences can also play a role, as autistic individuals or those with intellectual disabilities may be more likely to develop pica, especially if sensory exploration or rigid routines become part of daily life.

Studies have also reported associations between pica and conditions such as OCD and schizophrenia. In fact, the research states that these three conditions can overlap, showing that they may exacerbate each other.

Family environments can also influence pica, as limited supervision, chaotic living conditions, neglect or growing up around others who display similar behaviours may contribute to its development.

Cultural practices also matter, too, as some communities consume non-food substances in ways that are considered traditional or medicinal. Pica, however, refers to behaviour that falls outside these accepted practices and becomes harmful.

Is pica dangerous?

Pica can be dangerous, depending on what the person eats and how frequently the behaviour occurs. Some risks are immediate, while others develop gradually.

Knowing these risks helps highlight why early intervention is so important. Left unaddressed, pica can lead to complications that affect long-term physical and mental health.

How is pica treated?

Pica treatment usually works best when several professionals come together to support the person. The condition can stem from physical, emotional or sensory reasons, so the approach needs to reflect that rather than rely on a single method. Most people receive a combination of medical checks, behavioural support and emotional guidance, all shaped around their individual needs.

Checking for physical causes

The first step is understanding what might be driving the behaviour biologically. Doctors will look for nutritional deficiencies or other medical issues that could trigger cravings for non-food items. Low levels of iron or zinc are common findings and, once corrected, some people notice the urges’ ease. Any physical complications linked to pica, such as poisoning risks or intestinal problems, are also addressed straightaway to keep the person safe.

Behavioural support

Behavioural interventions are the cornerstone of pica management and have shown high success rates. Therapists may use techniques that reward safer eating behaviours or redirect the person when the urge appears. For those who seek sensory input, offering safer substitute items with a similar texture can help reduce the need to seek out risky objects.

When these plans are tailored to the person, they can lead to a substantial drop in pica episodes.

Mental-health guidance

Because pica can appear alongside conditions such as autism or OCD, emotional and psychological support plays a key role. Understanding whether anxiety, sensory overload or repetitive coping behaviours contribute to the urges helps guide treatment in the right direction.

There isn’t a specific medication for pica itself, but if the behaviour is linked to a separate mental-health condition, doctors may prescribe treatment for that. The main focus, however, remains on behavioural and psychological approaches because they address the root of the behaviour and help build long-term stability.

What are the next steps?

If you’re unsure whether you or someone you care about is dealing with pica, it’s worth reaching out for professional guidance rather than trying to figure it out alone. Symptoms can overlap with many other serious conditions, and a trained clinician can help you understand what’s really going on. They can also offer tailored advice on treatment options and practical steps to keep the person safe.

You don’t need a clear diagnosis to ask for help, and if something feels worrying or unusual, talking to a healthcare professional is the right next step. If you’ve noticed these signs in your children, it’s even more important to reach out for help, as these signs could indicate underlying issues that require quick interventions.